Sliding the cursor across the gray void of the screen, I feel my heart rate spike to 87 beats per minute as I hover over the ‘Send’ button. Seven days. That was the original plan-a week of breathing air that doesn’t smell like pressurized office carpeting and burnt coffee. But the longer I look at the request, the more those seven days look like a confession of laziness. In an environment where the ceiling is supposedly non-existent, the floor suddenly feels like it’s made of thin glass. I delete the ‘7’ and type a ‘4’. Then I stare at the ‘4’ for another 27 minutes. This is the psychological trap of the modern ‘unlimited’ PTO policy, a masterclass in corporate gaslighting that transforms a benefit into a high-stakes loyalty test.

I’m currently writing this while nursing a very specific kind of irritation. Yesterday, I tried to return a high-end blender I bought three months ago. I didn’t have the receipt. The clerk, a teenager who looked like he’d rather be anywhere else on the planet, gave me a look that suggested I was trying to dismantle the very foundations of capitalism by asking for a refund without paper proof. It was that same look of silent judgment I imagine my boss giving me when she sees a vacation request longer than a long weekend. We are a society obsessed with the ‘receipt’-the proof of our worth, the documentation of our earned rest. Without a hard number of accrued days sitting in a spreadsheet, we lose our permission to stop. We are floating in an ocean of ‘unlimited’ water, yet we’re dying of thirst because we’re afraid of how much it looks like we’re drinking.

The Baker and the Optics of Hunger

Consider Alex G.H., a third-shift baker I know who works over on 47th Street. Alex lives a life of rigid, beautiful clarity. He arrives at 11:07 PM. The flour is weighed by 12:17 AM. The ovens are screaming by 3:27 AM. When 7:07 AM rolls around, Alex is done. He doesn’t wonder if he should stay an extra 47 minutes to prove to the dough that he’s ‘committed.’ The bread doesn’t care about his optics.

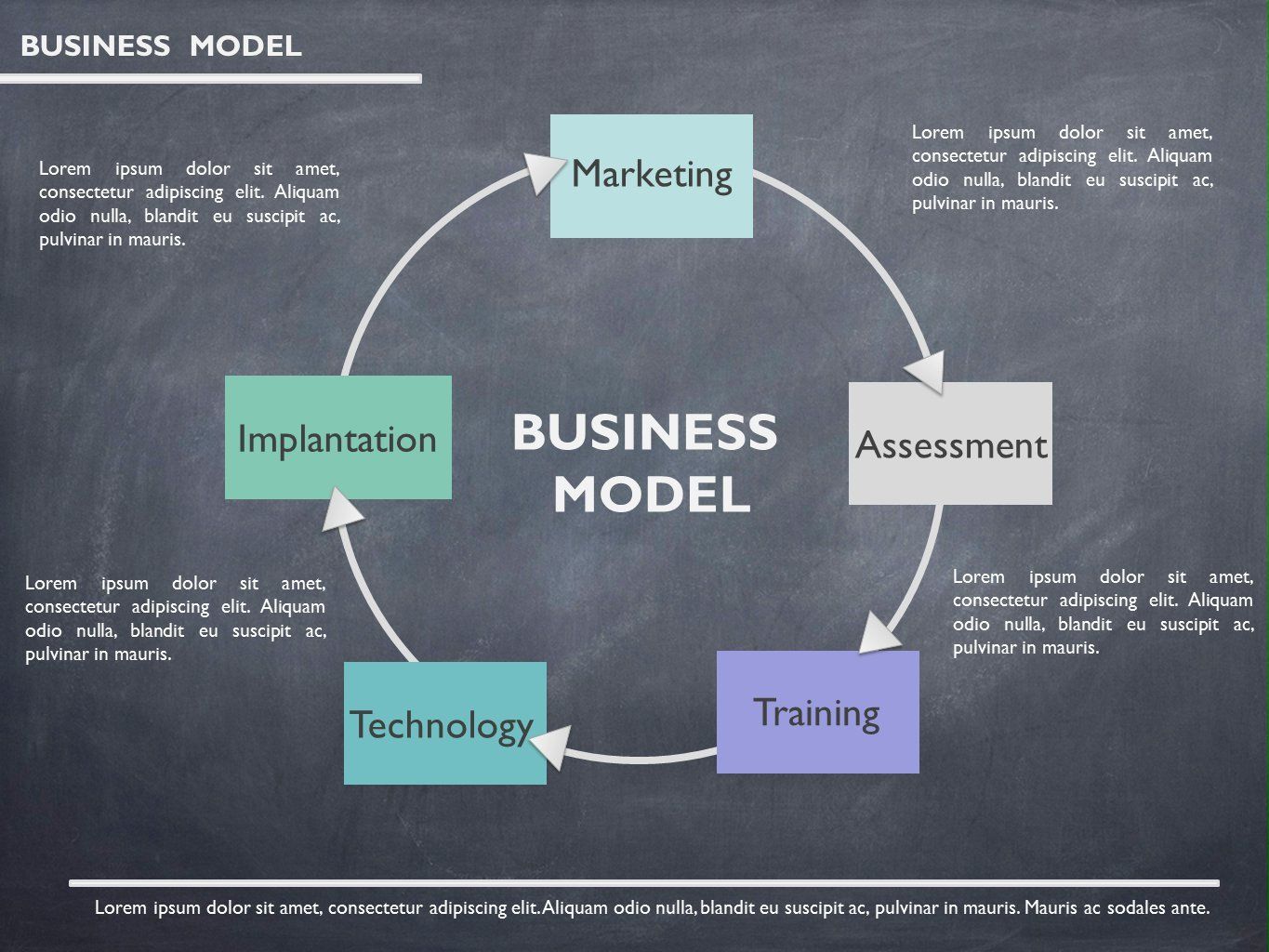

The Metric of Effort vs. The Illusion of Commitment

Days Owed (Liability)

VS

Perceived Risk (Guilt)

But in the world of unlimited PTO, we aren’t judged by the bread; we are judged by the appearance of our hunger. We stay late not because there is work to do, but because we are terrified that the person who leaves at 5:07 PM will be the first one let go when the next 7 percent staff reduction comes around.

The Financial Sleight of Hand

Unlimited vacation is a brilliant financial maneuver for the company, hidden behind a mask of radical trust. In most states, if you have 127 hours of accrued vacation and you quit or get fired, the company has to pay you for that time. It’s a liability on the balance sheet. By switching to an unlimited model, the company effectively wipes millions of dollars in debt off their books overnight. They no longer owe you anything. You haven’t ‘earned’ the time; you are merely ‘permitted’ to take it, provided it doesn’t conflict with the 147 different deadlines currently suffocating your team.

$127M

Wiped from Liability

(The Hidden Value Proposition)

It’s a gift that costs them less than nothing. In fact, studies consistently show that employees under unlimited policies take significantly less time off than those with a fixed 27-day cap. We are so afraid of overstepping the invisible line that we choose to stand perfectly still.

Becoming Our Own Taskmasters

I find myself overthinking every interaction now. If I take 17 days off this year, am I the ‘slacker’? If the average is 11 days, and I take 12, am I already on the list? There is a deep, soul-crushing ambiguity in these social contracts. We crave the receipt. We want the clerk to tell us, ‘Yes, you have this much credit.’ Without it, we are just guessing at the price of our own well-being.

This ambiguity isn’t just an accident; it’s a feature of the system. It keeps us tethered to our desks by our own guilt. We become our own taskmasters, policing our rest with a fervor that would make a 19th-century factory overseer blush.

Actually, I just realized I left my car lights on. Or I think I did. I have this recurring anxiety about draining the battery, much like I worry about draining my professional ‘capital’ by being human. It’s exhausting to constantly calculate the weight of your presence. This is why many are starting to look for spaces where the rules are actually clear, where the interaction isn’t a game of 47-dimensional chess. In a digital age where human relationships are fraught with unwritten rules and shifting expectations, there is a strange comfort in systems that behave exactly how you expect them to. People are finding solace in platforms like ai porn generator because, unlike a corporate HR department, the boundaries there are defined by the user’s own needs and desires, not by a hidden agenda designed to maximize ‘engagement’ while minimizing ‘liability.’ There is no judgment for wanting what you want, when you want it. It’s a stark contrast to the performative martyrdom of the modern office.

The Paradox of Unlimited Choice

I remember one specific Tuesday-I think it was the 17th-when the office was particularly quiet. Everyone was ‘working from home,’ which is corporate shorthand for ‘answering emails from the kitchen table so people know I’m awake.’ I wanted to go to the park. I had finished all 37 of my tasks for the week. But I stayed. I sat in my chair for 7 hours, staring at a spreadsheet that didn’t need me, simply because I didn’t want to be the one who wasn’t ‘there.’ If I had a set number of days, I would have used one. I would have felt entitled to it. But since I have ‘unlimited’ days, I felt entitled to none. It’s the paradox of choice taken to a lethal extreme. When everything is possible, nothing is permissible.

We have traded the gold standard of earned rest for a fiat currency of perceived loyalty, and the exchange rate is killing us.

Alex G.H. told me once, while he was scraping 77 grams of dried dough off a countertop, that he prefers the night shift because the expectations are honest. The sun isn’t there to lie to you about how much day you have left. In the corporate world, we are constantly told it’s a new dawn, a flexible future, a ‘family’ atmosphere. But families don’t usually track your 17-minute lunch breaks or expect you to justify why you need to see a doctor on a Friday. The ‘unlimited’ policy is the ultimate ‘cool parent’ move. ‘Do whatever you want,’ they say, while standing in the doorway with their arms crossed and a stopwatch in their hand.

Reclaiming the Receipt

We need to stop calling it a benefit. It is a debt-erasure program. It is a psychological leverage point. If we want to actually support employees, we should go back to the ‘old’ way-mandatory minimums. Tell me I must take 27 days off. Force me to leave the building. Give me a receipt for my time so I don’t have to carry the mental load of wondering if I’m stealing from the company by existing.

The Path to Defined Rest

Ambiguity (Status Quo)

Requesting favor; high mental load.

Mandatory Minimums

Claiming right; mental load transferred.

I think about that blender return again. If I had the receipt, I would have been confident. I would have stood my ground. Without it, I was apologetic, stuttering, and ultimately, I walked away with a broken blender and a sense of shame.

That’s what we are doing every time we ‘request’ a vacation in an unlimited system. We are returning a broken piece of ourselves to the company, hoping they’ll give us a few days to fix it, but we’re doing it without the receipt of earned time. We are begging for a favor instead of claiming a right. And the company, in its infinite ‘generosity,’ lets us feel just guilty enough that we’ll work twice as hard for the 4 days we actually managed to take.

|

I ended up not sending that request. I closed the tab and looked at my calendar. Maybe I’ll wait until the 27th. Or maybe I’ll just keep staring at the cursor until it blinks 777 times and I forget what the sun looks like. Is that the goal?

If we can’t define our boundaries, someone else will define them for us, and they won’t be doing it for our benefit. We are living in an era of ambiguous social contracts, where the lack of structure is marketed as freedom. But real freedom requires a floor to stand on, not just a ceiling that’s been removed to reveal an endless, cold vacuum. Why are we so afraid of the number 27? Or 17? Or 7? Numbers aren’t the enemy. Ambiguity is. And until we demand the return of the receipt, we will continue to be the customers who pay full price for a product we are too afraid to take home.