The Thud of Stagnation

The stapler hits the mahogany with a thud that vibrates through my teeth, a heavy, mechanical punctuation mark to a conversation that has been happening, in one form or another, for the last 103 days. Dave doesn’t look at me. He looks at the stack of invoices, his thumb grazing the edge of the paper as if he’s counting the fibers. ‘We’ve always done it this way,’ he says, and I can hear the capital letters in his voice. ‘It builds character. You kids want everything to happen in a blink, but there’s a rhythm to the manual entry. You learn the soul of the business when you touch the data.’ I’m staring at a coffee ring on my desk, wondering if he realizes that the ‘soul of the business’ is currently bleeding out through a series of avoidable clerical errors and 43 redundant spreadsheets.

I realized about twenty minutes ago that my fly was open during the entire morning stand-up, and that specific brand of quiet humiliation is currently coloring my perception of this entire room. It makes me feel exposed, but in a way, it makes Dave look even more armored. He’s wearing a suit that belongs in a 1993 boardroom, a polyester shield against the encroaching tide of cloud-based efficiency. He isn’t just a manager; he’s an Expert Beginner. This is a term I’ve been chewing on like a piece of tough steak. Most people think experience is a linear climb, a staircase to the stars. But for Dave, experience is a cul-de-sac. He didn’t get 23 years of experience. He got one year of experience, 23 times in a row. He mastered the basics of his role in 1999 and has spent the subsequent decades aggressively defending that plateau against any form of evolution.

“

The tragedy of the Expert Beginner is that they are too competent to be fired, but too stagnant to lead.

– Maria J., Virtual Background Designer

The Pixel Peepers and the Process Keepers

Maria J., our virtual background designer, once told me over a glitchy Zoom call that you can tell everything about a person’s psychological rigidity by the ‘room’ they choose to hide behind. Maria is the kind of person who notices the way shadows fall on a digital bookshelf. She pointed out that the Daves of the world always choose the most sterile, unyielding backgrounds-hyper-realistic glass offices or libraries full of books they’ve never touched. It’s a performance of authority that masks a deep-seated terror of the ‘new.’ Maria J. sees the pixels; I see the processes. We are both watching the same slow-motion train wreck. She’s currently working on a 3D environment for a client who wants to look like they’re sitting on Mars, and honestly, Mars sounds more hospitable than this office right now.

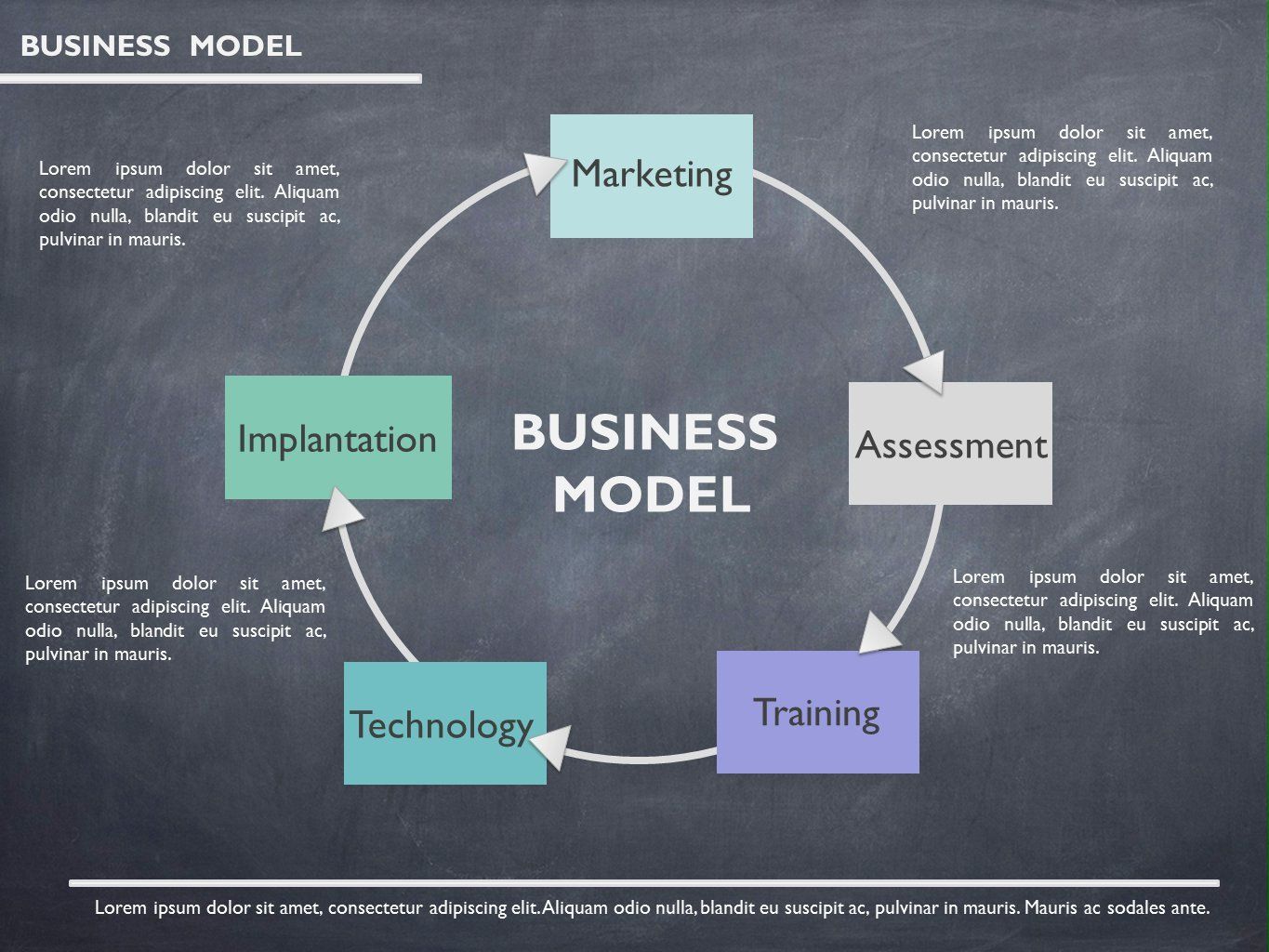

When I suggested the API integration that would save us 133 hours of manual labor per month, Dave’s eyes glazed over with a look that was part confusion and part predatory instinct. To him, an API isn’t a tool; it’s a threat to his sovereignty. If the reports generate themselves, what happens to the man whose primary value is ‘overseeing’ the generation of reports? The Expert Beginner survives by creating complexity where there should be clarity. They turn the simple act of data migration into a Herculean labor, demanding ‘character-building’ sacrifices from their subordinates. It’s a form of gatekeeping that relies on the friction of outdated systems.

The Cost of Friction

Quantifying the ‘vintage patina’ mistake ($2,003 discrepancy).

Career = Tenure

Career = Change

I find myself wondering if I’m being too harsh. Maybe the fly-open incident has made me cynical. But then I see the $2,003 discrepancy in the quarterly audit-a mistake that a simple script would have caught in 3 seconds-and the cynicism hardens back into a cold, clinical observation. We are being held hostage by a philosophy of ‘good enough.’ It’s the institutional equivalent of a necrotic limb. We know it’s dying, we can smell the decay, but the person in charge of the scalpel is the one who insists the gangrene is just a ‘vintage patina.’

This isn’t just about one man’s ego. It’s about how organizations promote people to their level of incompetence and then allow them to fossilize. We reward longevity over growth. We see a person who has stayed in the same chair for two decades and we call it ‘loyalty,’ when often it’s just a lack of options or an unwillingness to face the discomfort of learning. The Expert Beginner is the ultimate manifestation of the Sunk Cost Fallacy. We’ve invested so much in Dave’s tenure that we’d rather let the department sink than admit he’s no longer the right person to steer.

She’s currently working on a 3D environment for a client who wants to look like they’re sitting on Mars, and honestly, Mars sounds more hospitable than this office right now.

– Narrative Observation

In the middle of this thought, I accidentally knock a pen off my desk. It rolls under Dave’s heavy mahogany fortress. I don’t want to go down there. I don’t want to see what else is hidden in the dust of 1993. I stay in my chair. We need a way to bypass this friction. Forward-thinking organizations are already doing it. They are looking for ways to automate the mundane so the humans can focus on the complex. They use platforms like best factoring software to streamline operations that would otherwise be bogged down by the ‘Dave-factor.’ It’s about creating a system where the process is smarter than the person who is having a bad day, or the person who hasn’t read a technical manual since the Bush administration.

Measuring Lost Potential

The invisible turnover of idealistic interns.

Intern Spirit Retention (Last 3 Years)

37%

I think about the 63 interns who have cycled through this office in the last three years. They arrive with bright eyes and a mastery of tools that Dave can’t even name. They leave within six months, their spirits crushed by the weight of ‘building character’ through data entry. It’s a brain drain that the company doesn’t even track. We measure turnover, but we don’t measure the cost of the ideas that were never voiced because the speaker knew they’d be met with a ‘that’s not how we do things here.’

Key Insight:

Innovation is a fragile thing; it requires a vacuum of ego, something the Expert Beginner cannot provide.

Maria J. sent me a message. She’s finished the Mars background. She says the lighting is ‘desolate but honest.’ I think about the honesty of this room. Dave is still staring at the invoices. He looks tired. That’s the thing people don’t tell you about being an Expert Beginner-it’s exhausting. It takes a tremendous amount of energy to keep the world at bay. You have to be constantly on guard against anything that might expose your lack of knowledge. You have to turn every suggestion into a debate and every tool into a hurdle. It’s a high-stakes game of pretend that lasts for a career.

Eroding the Fortress

I wonder what Dave was like at 23. Was he the one pushing the boundaries? Did he have a ‘Dave’ of his own who told him that the fax machine was the pinnacle of human achievement and that email was a fad for the lazy? Somewhere along the line, he stopped being the disruptor and became the disrupted. He found a comfortable spot on the learning curve and set up camp, building a fortress of ‘wisdom’ out of the stones of his own limitations.

I’ve decided I’m going to tell him about the API again, but I’ll frame it as his idea. I’ll use the words ‘legacy’ and ‘optimization.’ I’ll pretend I’m just the humble scribe helping him realize his vision of a more ‘character-filled’ future. It’s a manipulation, sure, but in this ecosystem, it’s a survival tactic. You can’t fight a fossil with logic; you have to use the slow, steady pressure of erosion.

As I get up to leave-carefully checking my fly this time-I see a stack of floppy disks in a glass display case in the lobby. They are labeled ‘Core Values.’ It’s a joke, of course, a bit of kitsch left over from a previous office move. But as I look at them, I realize they are the perfect metaphor. The data is there, but the hardware to read it has been gone for years. We are walking around with pockets full of 3.5-inch solutions in a USB-C world.

I walk out into the sunlight, the humidity of the city hitting me like a physical weight. I feel lighter, though. There is a certain clarity that comes with identifying the ghost in the machine. Dave isn’t the problem; the worship of ‘time served’ is the problem. We need to stop asking how long someone has been doing a job and start asking how many times they’ve changed the way they do it. If the answer is ‘zero,’ then the 23 years don’t matter. They are just a very long, very expensive way of standing still.

Is the character we’re building worth the life we’re losing in these beige cubicles?

I think Maria J. would say no. She’d probably just tell me to change my background to something with more light.