The Deceptive Click

The click is the only real thing. The mouse button depressing, the soft plastic giving way, the cursor hovering over a checkbox for a moment before the world changes. A line appears through the words ‘Finalize quarterly report header font.’ A soft, satisfying chime plays through the speakers. The item vanishes. Plus ten points. Level up.

My system, a glorious web of interconnected apps and color-coded labels, says so. It has the receipts. But the big thing, the one project that actually matters, the one that requires more than 18 minutes of unbroken concentration, sits there. It’s a huge, cold mountain on the other side of the valley, and I’ve spent all day diligently, satisfyingly, picking up shiny pebbles at my feet.

The Disease of the Click

I just sent an email and forgot the attachment. The big one. After spending ten minutes crafting the perfect, deferential subject line, I failed the one simple goal of the entire exercise. The click of the ‘send’ button was just as satisfying as the click on my task list. The action was completed. The purpose was missed entirely.

We didn’t get here by accident. This is a manufactured addiction. The architecture of modern productivity is a brilliant, insidious casino designed to keep us pulling the lever. Every task manager, every project management suite, every “agile” board is a slot machine for accomplishment.

The ding of a completed task is the sound of a single cherry lining up. Inbox Zero is the jackpot, a fleeting, shimmering moment before the machine resets and demands more coins.

The game is rigged. It’s not designed to make you win at your work; it’s designed to make you keep playing the game of work.

Productivity Theater

This is a coping mechanism. We retreat into the comforting certainty of small, defined tasks because we are terrified by the ambiguity of the large, important ones. When you don’t know what truly matters-or you’re afraid to find out-the next best thing is to feel a sense of progress. Any progress. So you answer 18 emails that could have waited. You update a ticket with a comment nobody will read. You spend an hour reorganizing your digital files, a task with the same long-term impact as reorganizing your sock drawer.

That’s what we’re all engaged in. We’re performing busyness for an audience of ourselves. And I’m the worst offender. I’ll sit here and criticize these systems, and yet my personal calendar looks like the flight control panel for a lunar mission. It’s a festival of color-coding for 8 distinct life domains, with overlapping reminders and conditional formatting. I know it’s a game, and I still play it with the intensity of a grandmaster. The contradiction is the point. Knowing the trap is made of cheese doesn’t make the cheese less tempting when you’re hungry.

The Resonance of Deep Work

I was thinking about this while talking to Diana J.D. the other day. She’s a pipe organ tuner. Not a metaphorical one; she actually tunes the colossal, building-sized instruments in cathedrals. Her work is the complete antithesis of the modern knowledge worker’s experience. There are no small tasks. There is no checklist that can capture what she does. She can’t “clear her inbox” of dissonant pipes. Her project might be a single instrument, and it might take 8 months.

She has to account for the temperature and humidity of the building, which can change the pitch by a few cents. There are no points to score, no progress bars. For a full day, her only metric of success might be that a C-sharp sounds slightly less “troubled” than it did yesterday. Her work is monolithic, physical, and has an undeniable result. When she is done, a chord resonates through a stone hall in a way that can make a person weep. It is a feeling, not a metric. What does my completed to-do list resonate with? Nothing. It is silent. It is empty.

Initial Dissonance

Hours, sometimes days, to get a single note.

Subtle Shift

C-sharp sounds slightly less “troubled”.

Full Harmony

A chord resonates in a way that can make a person weep.

Diana often has to consult centuries-old schematics and maintenance logs, many of which are in German or French from the original builders. When I asked how she gets through the hundreds of pages of dense, technical material, she mentioned off-handedly that she uses a service to convert the scanned documents-the history, the specific metallurgical notes from 1888-into speech. She needs something that turns texto em audio so she can listen while her hands are occupied with a soldering iron or her ears are focused on finding the precise resonant frequency. Her tools aren’t a game; they are a bridge to allow for deeper, more focused work. They serve the mountain; they aren’t a collection of pebbles to distract from it.

Beyond the Sugar Rush

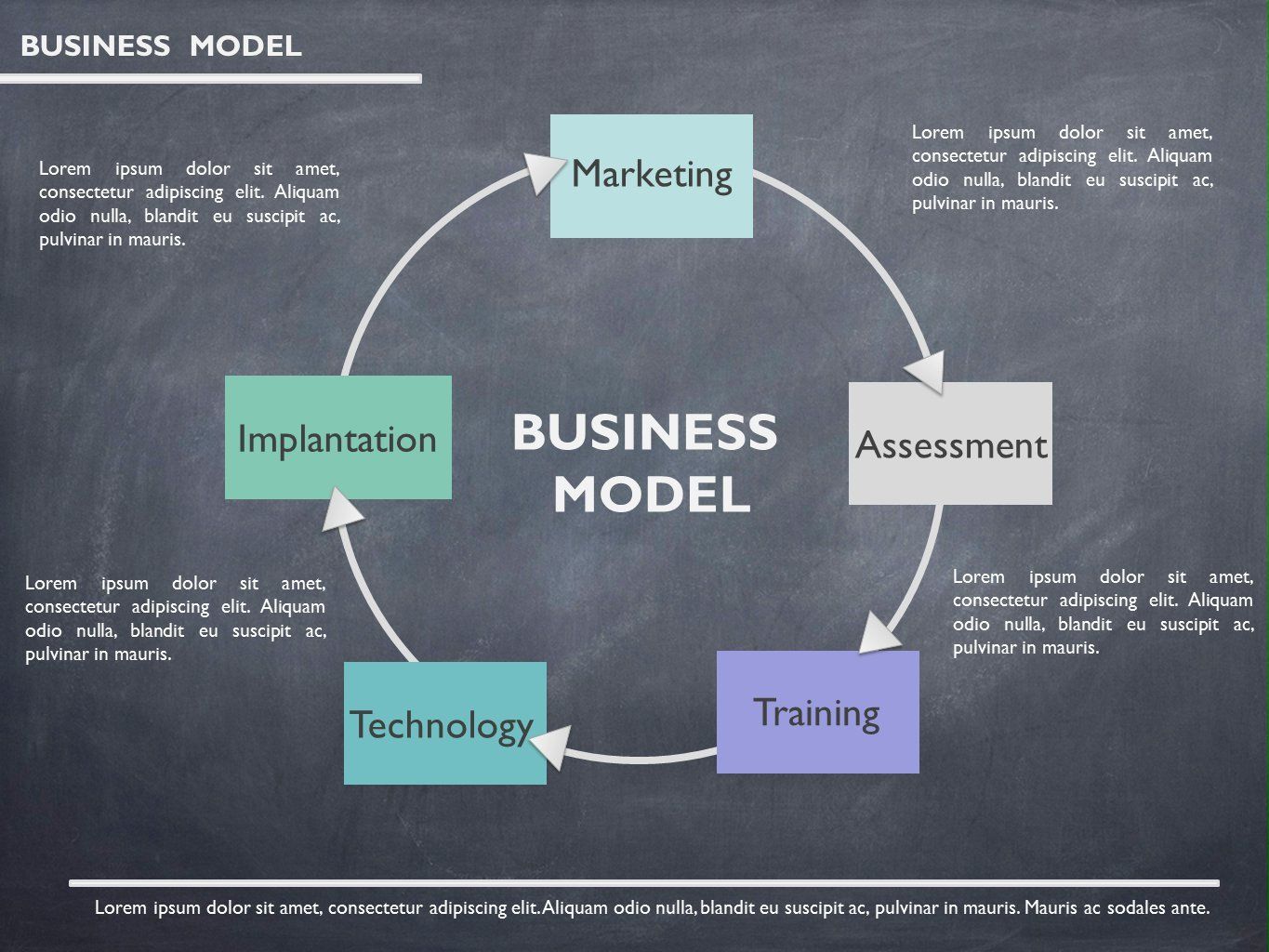

This is where we’ve gone wrong. Our tools are designed to create more pebbles. More notifications, more integrations, more things to check, more data points to track. We measure everything-time-on-task, tasks-per-day, emails-sent-except the one thing that matters: resonance. Does the work create a lasting, meaningful impact, or does it just make a satisfying “swoosh” as it moves from the ‘To-Do’ column to ‘Done’?

The screen shake when you land a heavy blow, the particle effects of an explosion, the crunchy sound of collecting a coin. Modern productivity apps are dripping with this artificial juice. Every cleared task is a little explosion of positive feedback. It’s a sugar rush. And we all know what happens after a sugar rush. The crash leaves you tired and lethargic, staring at the untouched mountain, wondering where the day went. You spent all your energy collecting 238 gold coins, but the dragon is still in its cave.

The Real Productivity System

Maybe the answer isn’t a better system. It’s not a new app or a more sophisticated methodology. I’ve tried them all. They all eventually become the same game. The game is to feed the system. To keep all the statuses updated, to tag everything correctly, to ensure your velocity chart looks healthy. The work itself becomes secondary to the administration of the work. The map becomes more important than the territory.

Abstract, administrative, distracting.

Real, resonant, tangible impact.

Diana doesn’t have a map like that. Her territory is the instrument itself. It tells her everything she needs to know. The dissonance is a clear signal. The harmony is the goal. Her ‘task list’ is written in the very air of the cathedral, in sound waves and vibrations. It cannot be faked. No amount of checking boxes will make a flat pipe sound sharp.